The Battle of

Seattle, 1856

The Battle of

Seattle, 1856

The Battle of Seattle was a January 26, 1856 attack by Native Americans

upon Seattle, a settlement in what was then know as the Washington

Territory.

Backed by artillery fire and supported by Marines from the United

States Navy sloop-of-war Decatur, the battle lasted one day. Two

settlers died. Native American casualties were believed to be 28

dead and 80 wounded. In the months leading up to the unrest, local

settlers were murdered, it was assumed by local Indians. Weeks

later, with a large number of Indians congregating in the area of

Seattle and rumor that there would be a large attack, the Decatur, with

attached Marines, was dispatched to the area.

Leading up to the engagement, it was reported, the Marines and officers

of the Decatur “put every energy in preparing for the battle.” The

divisions, skilled in the exercises of battle, occupied shore posts at

night and returned to the ship during the day.

The settlement, approximately three-quarters of a mile wide, was

defended by ninety-six men, eighteen marines, and five officers,

leaving a small contingent to guard the ship.

The night of January 25 set in heavily overcast and misty. While

uncomfortable for the crew and Marines on watch, the weather was calm –

advantageous for detecting the stealthy approach of the enemy.

At eight o’clock, two Indians closely wrapped in their blankets,

sauntered slowly by, apparently from the friendly Indian encampment in

town. When a pace or so away they were challenged to give their

names and business. They replied, “Lake Tillicum, and we have

been [out] to visit ...” They were ordered to “keep within

bounds, otherwise they would be shot.”

Within a hour an “imitation of an owl’s hooting was heard” directly in

front of the Marines and ship’s company, which immediately afterwards

received responsive hoots from both right and left making known the

enemy’s proximity. A “loyal” Indian scout was sent beyond the

settlement into the wilderness to collect information. Returning

two hours later, he reported “no Indians present in the woods and that

an attack that night was impossible.

Headquarters had been established at a home in the settlement, and

while there, the scout earlier sent into the woods displayed “a marked

change from his usual manner” giving an impression to one observer that

he was “beyond being further trusted.” Later, when the scout went

out to his own encampment he was followed. “He set out with rapid

steps toward his own encampment, muttering and gesticulating wildly,

and, when a dozen paces or more away, suddenly stopped, and, stamping

violently on the ground, turned and swiftly vanished in the direction

taken by the two Indians three hours before. Pondering over these

matters, the night quietly passed away, and while the vigilant

sentinels were mindful of the foe in front, they little dreamed of the

treachery being enacted in their rear.”

At midnight, beginning January 26, Indian leaders, along with the

“loyal scout,” met to decide upon a plan of battle. The council

decided upon “an indiscriminate slaughter of all the people found in

Seattle, including those belonging to the ship.” They believed

that they would win an overwhelming victory.

At seven o’clock that morning, the ship’s company and Marines were

moving back on board the Decatur to have their morning meal when they

were suddenly summoned on deck to take their posts at the settlement.

They are undoubtedly here at last,” an officer told the Capitan, “but

probably will not show themselves till night.”

The Capitan ordered that the men remain at their posts but to sleep in

order to be rested and ready when the Indians appear.

“First, however, I will go to the south end and have the howitzer lodge

a shell in Tom Pepper’s house to see if they are there,” the Capitan

ordered. At the same time there was a crash of muskets from the

entire rear of the town, “while a tempest of bullets swept through the

village in unison with the deafening yells” of Indians.

Leaving the third division and marines to hold the Indians in check,

attentions were turned to the south, where large numbers were engaged,

and “neither party could approach the other without incurring certain

destruction.”

The roaring of an occasional gun from the ship, belching forth its

shrieking shell, and its explosion in the woods, the sharp report of

the howitzer, the incessant rattle of small-arms, and an uninterrupted

whistling of bullets, mingled with the furious yells of the Indians,

was a scene long to be remembered by those who were there.

The firing had reached a crescendo on the part of the Indians assembled

on the hillsides and in the valley near a swamp. Desperate by

blunders committed earlier, the Indians now seemed bent upon remedying

their errors by raining bullets upon the little band of men holding

them at bay.

Three o’clock came, and with no sleep or food for almost a whole day,

came exhaustion for the men. But the guns of the Decatur

continued to fire solid shot, shells (which exploded after impact),

grape shot, and canister shot into the trees sheltering the

attackers. Marine fire along with the Decatur’s guns kept the

Indians at a distance. Sporadic exchanges of fire continued until

11:45 a.m. when the Indians apparently paused to eat. The settlers took

advantage of the lull to evacuate women and children to the Decatur and

another ship. When settlers attempted to retrieve arms and

valuables from their abandoned homes, the Indians resumed firing. The

battle continued until 10 p.m. when the last gun was fired, and the

battle of Seattle was over. The Indians had been defeated and

turned back.

The number of Indians assembled before Seattle is not known but it is

estimated that there were 1,100 to 2,000. Settlers suffered no

more attacks in Seattle.

Compiled by Kevin

Sadaj from the following Sources: Wikipedia; US Marine Corps

Heritage Center; Department of the Navy Historical Center from an

article Reminiscences of Seattle, Washington Territory, and the U. S.

Sloop-of-war Decatur, during the Indian War of 1855-56, by the late T.

S. Phelps, Rear Admiral U. S. Navy, originally appearing in United

Service Magazine.

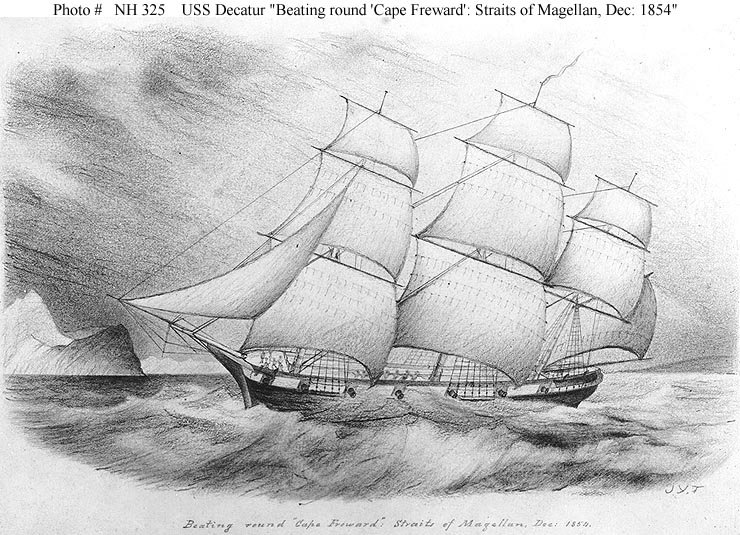

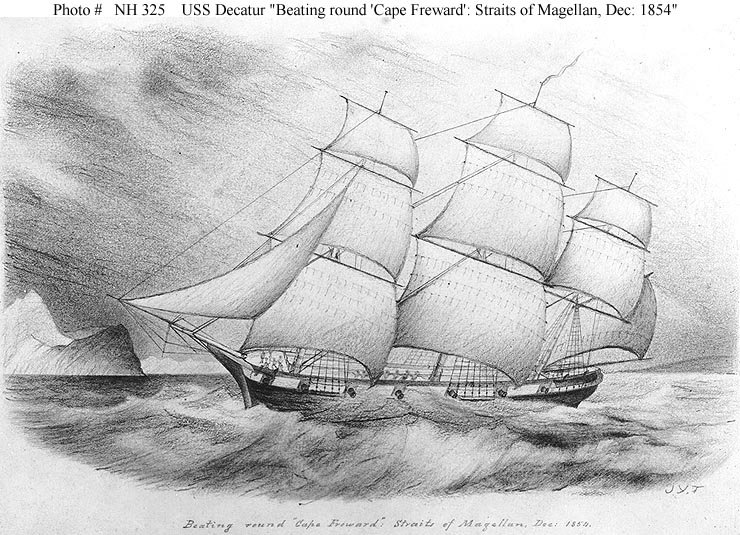

Pictures:

United States Navy sloop-of-war Decatur

Battle of Seattle Painting by Emily Inez Denny, Courtesy MOHAI

The Battle of

Seattle, 1856

The Battle of

Seattle, 1856